Gauteng gastrognome Victor Strugo calls Cape Town and Johannesburg “the Ying and Yang of SA. The city of Pink and the city of Gold, where waiters try to please rather than look pleasing.” If Cape Town is the Spanish court of Ferdinand and Isabella, then Johannesburg is a culinary Christopher Columbus “searching for sophistication and innovation.”

Simba Chips experience a more practical differences between the two: packets of pretzels made in Cape Town explode when transported to Johannesburg because of the difference in air pressure. Similarly, bags of chips made in Johannesburg arrive shrink wrapped when shipped to Cape Town, which explains why the company runs two factories.

This difference in air pressure could also explain the difference in wine choices between the two metropoli. Leading the existence of a baked bean in a tin can, shuttled between the two cities once a week, one lesson I’ve learnt is how fruity and acidic wines perform better in upcountry tastings while wood and tannin hold sway at the seaside – a physical expression of Victor’s pink and gold dialectic.

The difference in air pressure is due to a 1500m difference in altitude between Hiveld and coast, which results in physiological differences in how wine is perceived by the nose and taste buds. Wine for Dummies advocates coastal dwellers drink reds on drier days when the barometer registers low pressure – the usual state of play upcountry while wine educator Ed McCarthy claims a general rule of thumb: “wines taste better in thinner pressure and low humidity.”

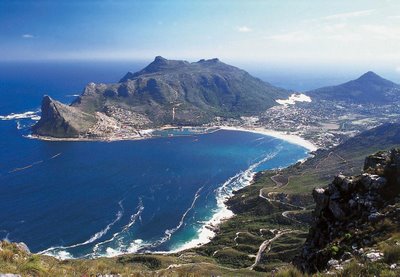

Which poses some interesting challenges for the Cape (sorry, SA) wine industry. With Gauteng accounting for roughly two thirds of the national fine wine market, it makes sense that the major tasting competitions such as the National Young Wine Show and Veritas be either held up country like the Juliet Cullinan Wine Connoisseur Awards or on top of Table Mountain, which is as close as Cape Town comes to Johannesburg’s situational variables.

The raft of competitions like the Diners Club Winemaker of the Year Award and Michelangelo International Wine Competition, which started out upcountry, should return forthwith if their selections are to be relevant to the largest consumer market.

Similarly, winemakers should be aware that the majority of their wines will be drunk in a reduced pressure environment as compared to the cellars in which they were made. Perhaps a special high altitude style could be developed for upcountry consumers living in a deflated milieu as compared to coastal pressure cookers.

Certainly airline wine selection exercises such as those staged annually by SA Airways, should happen upcountry, which is far closer to cruising altitude than any coastal venue. Similarly the Cape’s burgeoning cottage industry of consumer wine guides would make a lot more sense if the tastings were held up North. A change of venue would also introduce some fresh palates, which would be a bonus. With upcountry folk used to boiling their eggs longer, accustomed to drinking their rooibos tea at less than 100 degrees and needing lower octane petrol to run their cars, high altitude wines are a physical necessity for the nation’s largest market.