Having been a winewriter for almost two decades, I’ve decided to become an artist. My first exhibition is as part of a group show at Monte Casino which opens at 18h00 on Wednesday 18th June. Old habits die hard and I couldn’t resist writing it up for the June edition of Good Taste magazine.

The Buddha of biodynamic winemaking, Nicolas Joly, may call himself “an artist of the earth” but is David Finlayson really on the same wavelength as David Hockney? Is the wine cellar the new art studio? While icon wines from rare vintages may attract silly money on auction, just like the big cat sculptures of Dylan Lewis did at Christie’s in London last year, no art critic would dare to score William Kentridge 17 out of 20 or award him a rating out of 100 in the same way that wines are routinely assessed. Conversely, while many a parent may claim their child can paint better than Pablo Picasso, Jean-Michel Basquiat or Tracy Emin, few would claim their offspring could produce an Yquem or a Bollinger.

That said, wine and art do have a lot in common. There is similar confusion over exactly what makes fine art with Damien Hirst’s diamond encrusted skull, For the Love of God, sold recently for $100 million, a good example. Over in the SA spittoon, the pointy-tongued pundits of the Platter guide rated the Woolworth’s selection of Duncan Savage’s Cape Point 2007 Sauvignon Blanc a full house five of stars while the pundits of WINE magazine over in Pinelands scored the same wine a lowly one star, at the same time. And the goalposts of wine and art change continually. Where have all those acidic Premier Grand Crus of the seventies and eighties gone or the magnums of Blanc de Noir? The same way as the voluptuous Venuses of Rubens, squeezed out of the beauty stakes by Twiggy, Kate Moss and a new aesthetic heroin-chic model.

But can wine ever be art? Wine is above all, a natural process. As Paul Draper, philosopher and winemaker at Ridge Vineyards in California puts it “what is fine wine all about? Let’s start from the point that making a wine is a natural process.” Just like the works of Andy Goldsworthy, the land artist who sculpted a snake out of sand at Donald Hess’ art gallery at the Glen Carlou winery earlier this year after filming the shadows cast by leaves in a bubbling brook.

Draper claims “for me, it’s a bond of trust with the soil, the place, the land itself” which sounds a lot like an artist’s statement from Strijdom van der Merwe whose red flags on the barren hillside above the Rooiberg Winery do so much to chirp up the start of the Robertson wine route. As do those waving yellow hands on the R44 (that I thought were an ad for Simba Nik-Naks) in the vineyard of Oude Libertas in Stellenbosch.

Then there is the temporal nature of wine. Even the greatest vintages eventually turn to vinegar. Destroyed just like the Bloubergstrand sculptures of Van der Merwe when the tide comes in, while the Last Supper of Leonardo needs to be continually refreshed or it will simply fade away and where would Dan Brown and his conspiracy theories be then?

In a conversation with Andrew Jefford, the UK’s best wine writer by a country mile, in Questions of Taste: the philosophy of wine (edited by Barry Smith, Signal, 2007), Draper agrees with Jefford’s assertion that “greatness in wine comes primarily from its place of origin, but requires the will and experience of the wine grower to be able to express its greatness. Wine is not, therefore, an artistic creation like a piece of music or a sculpture.” Jefford is rolling out the old terroir hobbyhorse and taking it for a ride.

Draper agrees. “Wine is not a created work. What we do is more akin to what a performer does with a piece of music.” But then as Marcel Duchamp proved a century ago with his ready-mades (including a urinal he cheekily titled “fountain”) while some winemakers (or winegrowers as Draper prefers to be known, or “nature assistants” as Joly puts it) and some wine writers may declare than wine is not art, artists are quite at liberty to call anything they like, art, including the fermented fruit of the vine.

So when the invitation to exhibit at the Sixth Sense art exhibition at Monte Casino fizzed through the internet and into my in-box, my ears pricked up. The exhibition is being held in conjunction with the annual conference of PRISA (the PR Institute of Southern Africa), which this year has as theme Communication – the Sixth Sense. In addition to the aforesaid exhibition, there will be “an environmental ballet created on this theme” plus “a mega-fashion show in which garments will depict the six senses.”

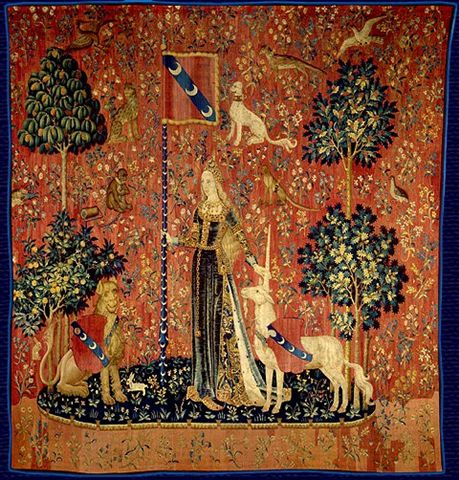

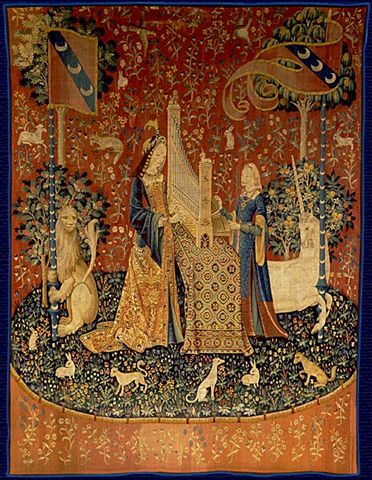

The point of departure for the exhibition, ballet and fashion show is the medieval tapestry La Dame à la Licorne, the maiden and the unicorn, which has the six senses as leitmotif and is to be seen at the Cluny Museum in Paris. One of the masterpieces of medieval art, it would not look out of place in the faux-medieval piazzas and palaces of Monte Casino.

The six senses are the traditional five: touch, taste, smell, hearing and sight plus a sixth sense “which arises from the interaction between stimuli from the outer world and the inherent knowledge of the inner world.” Wine obviously titillates the five traditional senses while terroir makes a strong case for informing a sixth. As has been proved many times in experiments involving cat-scans and the like, the brain’s enjoyment of wine is not totally derived from sensory input. Prior knowledge – knowing the wine is expensive, for example – improves the tasting experience no end.

Having bought Lemoenfontein, a modest wine farm on the Paardeberg, last year, I decided to make the most traditional wine I could from ancient bush vine Pinotage grapes growing on the farm’s steep slopes. The connection between wine and tapestry is compelling. A maiden vintage (la dame) from a mountain famous for quaggas – the boere version of the mythical unicorn, and also extinct – the grapes were harvested on St. Valentine’s day, which could explain the dreamy lovelorn expression of the girl depicted in the tapestry.

Made together with three friends (Stellenbosch winemakers Donovan Rall and Johan Kruger) in the Nabygelegen cellar of James McKenzie in the Bovlei valley above Wellington, the co-operative nature of the winemaking process mimics the teams of weavers responsible for the tapestry. Both are handmade with no artificial technology used at all – the wine was fermented using wild yeasts and matured in third-fill French oak barrels, confirming the French connection.

Exhibition curator, Mixael de Kock, unwittingly supplies the final thread as his CV lists “380 major national exhibitions between 1976 and 1992 – the majority of these exhibitions under the label of Stellenbosch Farmers’ Wineries’ wines.” So it’s hard to imagine a more complete artwork in accordance with the exhibition brief than a barrel of Lemoenfontein Pinotage which we’ve decided to call “the six P’s”. The first five, arranged alphabetically are Paardeberg, Pendock (the artist), Perold (the pioneer who produced Pinotage by crossing Cinsault with Pinot Noir), Pinotage and PRISA. The final P is a pee, the ultimate end-state of the work once it has passed through the body.

Of course sale of the work to a collector (or failing that, a drinker) might be a tricky issue as the exhibition is unlikely to have liquor license. But then, this barrel is a work of art and any resemblance to a barrel of wine is purely coincidental.