By Leah van Deventer

The Bartender Accolades and Recognition (BAR) Awards, which normally leave local movers and shakers in good spirits, have in true 2020 fashion had the opposite effect. Sponsor brands are outraged, winners feel cheated and people generally seem to be fed up. So what went awry?

THE BACKSTORY

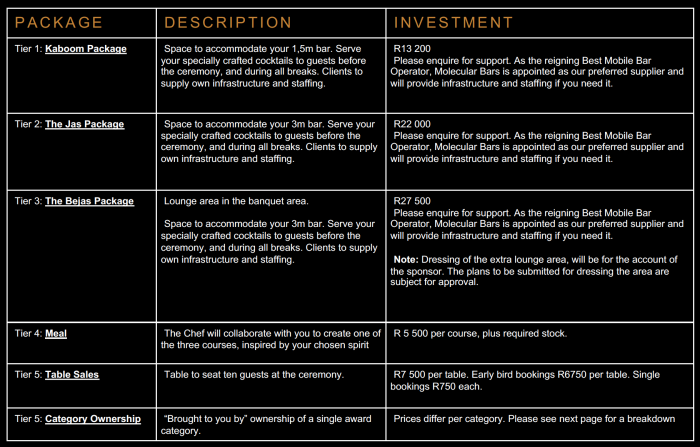

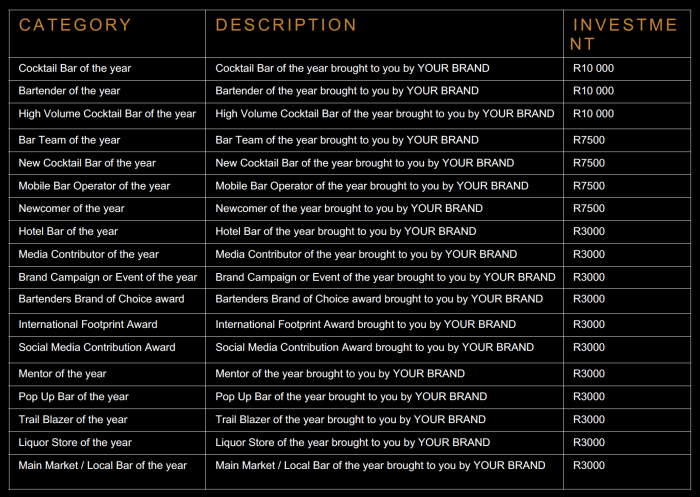

The awards were initially set to be a glitzy gala affair in March, at Joburg’s Maslow Hotel. In the preceding months, the BAR Awards team – directed by Travis Kuhn, Leigh Kuhn, Howard Ross-Simms and Ophelia Ross-Simms – had been hustling for investments. Brands were invited to sponsor an award, feature their products in a mobile bar, collaborate on a meal course and purchase tables … or any combination thereof.

The BAR Awards team managed to raise over R400,000 toward hosting the event. But then, of course, Rona swept in, and group gatherings were verboten. The awards were ultimately restructured to be virtual, with would-be attendees watching independently online in September.

The investor brands included Diageo, Pernod Ricard, Halewood, Truman & Orange, Liquid Concept, Rémy Cointreau, Copper Monkey, The House of Angostura, Edward Snell, Covert, Sir Fruit, Inverroche, Beam Suntory, Hope Distillers and News Café.

PROBLEM 1: THE BRAND INVESTMENTS

Instead of refunding the brands, the BAR Awards team decided to set up an industry fund. A presentation to the brands stated, ‘We aim to produce the awards at a reduced cost and the combined surplus budget will be distributed across the categories and disbursed to all finalists in each category … For us, this is the boldest statement we can make about our belief in this industry, and we invite you and your brand to join us!’

Sounds great, right? Except the word ‘invite’ is misleading. The brands weren’t invited at all – in reality they were simply told the monies they’d paid for the event were going to be given to the finalists (note, to ALL the finalists, but more on that later).

It’s all very well to set up a fund, but contribution should have been voluntary. Indeed, while the BAR Awards team keep insisting the support was ‘unanimous’, several brands requested refunds, and they were either blatantly ignored or flat-out refused.

The issue was not with the award sponsorships, as they would go ahead in the virtual event, but with paying for mobile bars, courses and tables, which they were no longer going to benefit from.

One brand representative, who chose to remain anonymous, said, ‘I sent numerous emails and tried calling to request either a full refund, or at least partial. This was ignored many times. It was also awfully disappointing that with the amount of money we invested, the only thing we received in return was a logo that appeared for five seconds at the beginning of the [virtual awards] presentation.’

The amounts invested by the various brands ranged from R3,000 to R70,000. At a physical event, brands that invested more would have received more; at the virtual event, they all received the same exposure, except some brands spent a whole lot more than others getting it. The press release that went out about the fund also simply listed the brands, not accounting for the extent of their sponsorship. Fair? Nope.

PROBLEM 2: THE FUND RECIPIENTS

Now, the BAR Awards team had promised that all finalists in the 19 categories would receive a slice of the fund. However, six of the categories were later excluded, as those winners and finalists were somehow deemed ‘less vulnerable.’

In addition, instead of simply divvying up the total fund among the nominees – preferably with the winners taking a bigger cut than the finalists – everyone had to apply.

A total of 39 businesses and individuals qualified to apply; by some strange logic, business could apply for two portions of the fund, if they had been nominated in two categories, but individuals could only apply for one, regardless of nominations.

There were 19 recipients of the fund. Here they are:

Said Peter Lebese, winner of the Social Media Contributor award: ‘I feel a bit cheated as in a competition a winner should always get a prize. I misread [the mail about applying] as I thought if you won you automatically get part of the fund, but I come to see that was not the case. Winners need to prove they deserve a cut.’

An anonymous winner said, ‘While the fund was welcome, [it] didn’t seem fair to have to apply for it if the fund was for winners and nominees anyway … also why were some not eligible for the fund if it was meant to uplift the industry. What criteria made them less deserving?’

Leighton Rathbone, Beverage Manager at Gigi Bar, winner of Hotel Bar of the Year, said, ‘I do think the rules were a bit exclusive; just because somebody maybe works/worked for a multinational company or hotel group doesn’t mean they [were] taken care of during lock down, or even after. But I understand that this was a first time and it will always be a very hard thing to police.’

‘I am extremely grateful to be awarded Bartender of the Year and International Footprint Award. I love our industry more than I could possibly explain and I will continue to give back,’ said George Hunter. ‘However, I am very disappointed in the SA BAR awards program currently. No prize/grant money was received for either [award] that I won.’

Note that BAR Awards founder and director Travis Kuhn awarded himself three slices of the fund via his businesses, totalling R31,500. A bold move, given that 13 winners weren’t awarded anything at all.

PROBLEM 3: THE FUND VALUE

In a press release, Travis Kuhn said, ‘The awards are run on a really tight budget, and we did whatever we could to limit expenses to ensure a surplus.’

As mentioned above, the brand buy-in came to around R400,000. The fund totalled R199,500. So where’s the rest of the ‘surplus’ cash? Could it possibly cost R200,000 to host virtual awards?

In the fund presentation mentioned above, the Bar team had said, ‘All contributions will be made public, and full budget and expenses revealed to ensure transparency … all contributions from each sponsor will be published.’

At the time of writing, more than two months after the virtual ceremony, the promised information had not been delivered, and certainly not published.

In fact, the Bar team specifically asked that the full fund amount NOT be published, ‘We purposefully didn’t include the amount that was shared between the winners that applied for this fund [in the press release] so you are welcome to ask the winners about it, but if at all possible not to publicise.’

Why on earth not?

On this, another anonymous brand representative said, ‘To say we are fuming about this does not even begin to describe it, and believe me, we are not the only people involved that are very upset. This whole situation stinks of something extremely fishy. Nobody knows where any of the money went to.’

PROBLEM 3: THE WINNER’S TROPHIES

Ah, the trophies. A prickly topic all round. Part of the brand sponsorship of an award meant the brand’s name was to be engraved on a trophy, alongside the winner. These trophies get proudly displayed in venues, earning the brand ongoing return on investment.

Not so.

The winners, in fact, only received certificates – unframed, to boot. Both brands and winners were exceedingly bleak about this.

Lebese said, ‘Truly speaking being nominated is awesome but I feel like the fact that no gala was held this year it’s a bit sad that we get certificates and no trophies. It’s a bit of a step back and just feels a bit weak. I feel they could [have] made the effort for trophies.’

Rathbone said, ‘Myself and my team are very happy to have won the category [but] I won’t lie, I was upset at the lack of trophies, as it would have been our first one, and I kind of assumed they would have been made by the time lockdown happened.’

Said one brand representative, ‘The awards [were] only cancelled a few days before the event, if I remember correctly. These trophies should all have already been purchased even if not yet engraved. So essentially a few days before the event they didn’t have trophies yet, seems strange. I have chatted to a number of the [award] winners, and they too are appalled to have received nothing.’

Another brand representative confided that when they approached the BAR team about cancelling their award sponsorship, they were told that the trophies had already been purchased, presumably as a way to prevent them from pulling out.

So what happened to the trophies?!

PROBLEM 4: THE JUDGING CRITERIA

Unlike similar awards around the world, the BAR Awards are based purely on votes from invited industry members, without any auditing by judges. This essentially makes it a popularity contest.

The Spirited Awards, for example, take nominations from the public. Each nomination has to include a motivation, explaining why said nominee is deserving of an award. These nominations are then judged by a panel of experts – chosen and overseen by academy chairs – who vote for the worthiest candidates, based on merit.

Judges also have to disclose any affiliation they have to a business or individual nominated, or recuse themselves from voting if there’s a conflict of interest. Furthermore, the category parameters for the BAR Awards are unclear, and in some cases nonsensical.

Said Lebese, ‘I get the awards are for a good and positive energy in our industry but the fact that we don’t have a solid criteria per group and panel of finalist judges kind of tweaks me. I feel like the past three years of the awards [we’ve] been finding and growing the awards to be something great, whereas now it seems like it’s a thing of popularity and gloat, not growth and inclusion.’

An anonymous winner agrees: ‘While the awards are great for bringing the industry together [they] also raise too many question marks … it seemed like a popularity contest. A better judging system should be put in place otherwise it could divide the industry, which it seems to have done.’

Cassandra Eichhoff, Mentor of the Year, added, ‘The most heard comment about the awards is that it is a popularity contest, which most probably is true as the voting panel is selected and kept within the industry. There are ways to avoid any type of favouritism and it starts by the setup of the awards criteria.’

‘I would like to see the BAR Awards expand in a way where certain KPIs are set out well in advance and for venues/brands/individuals to be able to participate evenly and work towards a common goal. This should encourage healthy competition, a boost in service standards and overall industry growth as more venues will be exposed to the scene,’ she continued.

WHAT THE BAR AWARDS TEAM HAD TO SAY

When given an opportunity to comment on the above, the BAR Awards team confirmed that they didn’t ask the brands’ consent to create the fund … because they ‘didn’t have to’. The brands had signed a contract with a force majeure clause, forgoing any right to a refund should unforeseeable circumstances prevent the BAR Awards from fulfilling a contract, so this is true, but was it smart, or indeed kind?

‘The few brands who requested refunds were informed of the force majeure clause and also made aware that we could not refund one brand and not all others, this would dismantle the idea of the fund’, they said.

Many of the brands themselves were experiencing financial difficulties, with several even retrenching. To force them to give away up to R70,000 just because the contract permitted it seems both mean spirited and short-sighted, given that these same brands are expected to support the awards in the years to come.

The team also maintains that the R200,000 that didn’t do into the fund was used for expenses, and that they received ‘zero profit.’ Well, we all know non-profits pay their staff, so the question here is how much of those expenses were for services rendered by the BAR Awards team.

To this, the BAR Awards team said, ‘The brands will receive an info pack this week which will include information of how the money was allocated.’