A unique visitor centre adds lustre to India’s west coast, writes Clifford Roberts.

I’m mid-sentence when a soft voice behind and to my left apologises for the intrusion. Waiter. Would sir like anything else from the bar? I check my watch. 10:40pm. Seriously? Alas, a curfew on the sale of liquor is in place until India’s national election has been concluded; even at here at the country’s Party Central – Goa, where I’m at.

Up and down the beach, where tourists have come to jol between stints of sun-drenched recovery and post-binge yoga since forever, it’s like an Eskom roundhouse tonight: lights-out, one-time.

Fortunately, the booze story takes a bit of an upward turn here. The province has just added to its attractions of palm trees and powdery sea-sand India’s first visitor centre at a single malt whisky distillery.

The centre is my reason for being here. My interest was piqued at a tasting of Paul John Indian single malt in Cape Town last year.

A few months later, I stepped off the plane, my body meeting the wall of hot, steamy air like a fly colliding with syrup. But after suffering two seasons of drought in Cape Town, I enthusiastically drank in the landscape of thick green jungle. Extended villages exist along roads that snake beneath the leaf-cover, colonial building styles still perceptible as Portuguese though losing ground to natural decay and indigenous flair.

Goa lies on the Western coastline, bordering the balmy Arabian Sea that attracts over two million visitors every year.

I’m equally (characteristically?) thirsty when the car slows to a halt outside large, iron-wrought gates in a neighbourhood that didn’t fit. Cuncolim is a gritty industrial area that has been home to the distillery since the early 2000s. Its visitor centre has made it stand out even more. Designed by a Goan architect in a Portuguese style with give-away arches and clay roof tiles, the airy building is a resplendent canary yellow. A pair of elephant statues at the entrance door remind you of where you are.

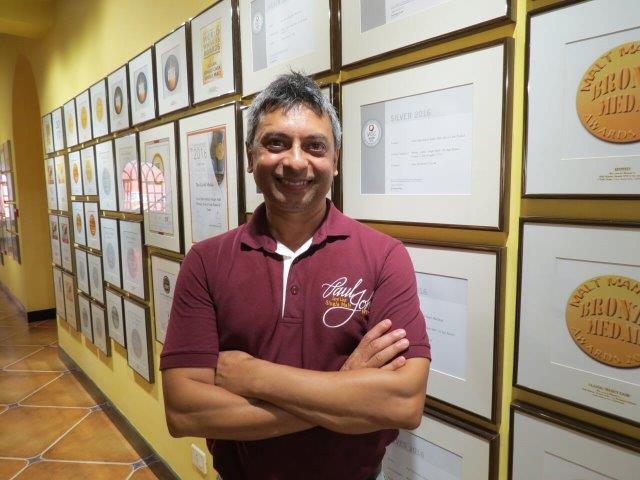

A passageway to the heart of operations does too, where the proof of more than 260 awards including a trophy from South Africa, since the official launch of Paul John single malt in 2012 are displayed.

Really, the story of Indian single malt is one of pure gumption considering the world’s much older and more established alternatives. Selling whisky in India, one of the planet’s biggest consumers of the spirit is one thing; taking on the whisky gods of Scotland and Ireland is another.

“When we started in single malt, the taste was outside of India,” says Heemanshu Ashar, head of marketing for John Distilleries, explaining founder Paul P John’s strategy to launch in London rather than his home country. The company had been around since 1992, but its entry to premium whisky only came in 2004.

“By that time the US, UK and Germany were looking for something different because the Western world’s palates had become jaded. Japanese whiskies arrived with the lightness of a feather, but extremely aromatic.

“And now for the first time in India, the single malt category is growing in popularity.”

Alongside Heemanshu in the cooled entrance hall is distiller Michael d’Souza, the gentle man with the easy smile I’d met at that first tasting when he toured South Africa. He greets us and turns to lead the way. First, there’s a video to set a proud tone for whisky of (almost) all-Indian ingredients: high quality six-row barley from the foothills of the Himalayas; yeast; and, natural spring water that filters through Goa’s ancient bed of volcanic rock. Peat is imported from Scotland’s Isle of Skye and Highlands.

We make our way through the buildings to a room stacked to the roof with bags of malted barley. “GMO’s are banned in India, and that applies to the grains too,” Michael tells us, adding that their best supply hails from Rajasthan. “The ideal climate is characterised by dry, cold winters when the barley is sowed, and development occurs during the hot months.”

As Michael talks, occasionally scooping grains to pass around, two men in dhoti’s – traditional garb like a sarong – manhandle sacks to a chute that sends the barley into the system.

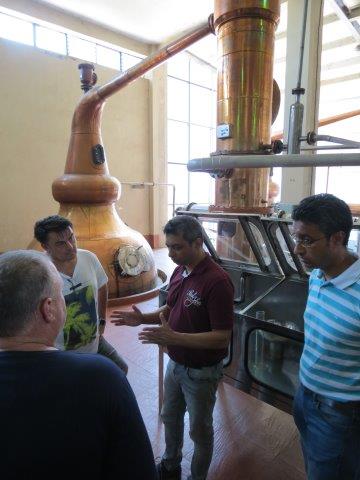

We track its route into the mash house where it joins water and yeast to ferment and produce a sweet, milky liquid called the “wort”. The wort is transferred to four large pear-shaped copper pots — the treasured potstills. The whole process is governed by ISO certifications, including one for environmental management.

The patchwork visible on the copper surfaces tells the story of daily alterations the distillery made to achieve the desired flavour profile.

The heat is stifling, and it shows. Thankfully, our hosts produce handfuls of napkins for us to pad gushing brows, necks and temples. To the temperature is added the smell of maturing whisky when we step into a maturation warehouse that’s home to 6 000 barrels, most of which have been purchased from American distilleries Heaven Hill and Buffalo Trace. Here, three men use a pulley to hoist barrels to a fourth deck – about midway up the stack – and line them up before filling.

It’s here that one of the important differentiators happens for Indian whisky – higher temperature and humidity increases the pace that the wood flavour influences the spirit. The appealing result: whisky that tastes older than it is. An underground warehouse where more barrels lie, provides a palette of slower developing whiskies that allows for greater diversity of blending before bottling.

I’m grateful to return to the air-conditioned interior of the centre, where Michael sets about conducting a tasting. It’s a rare opportunity to taste the full range, including the distillery’s tribute to when India became the first Asian country to achieve orbit around Mars in 2013.

The experience is dizzying – the heat, humidity and the morning’s breakfast curry don’t help. I think to myself that more than anything, single malt makers are afflicted with a snobbery that succeeds too often in putting fear in most people. Heemanshu pats me on the shoulder re-assuringly. “Goa is not just a place; it’s an experience and that’s what you get in our whisky.

“Paul John single malt is that Goa feeling; it’s all about palm trees and beach sand,” he says.

Now what could be friendlier than that?