Talk about synchronicity. Sour Grapes is published on 20 October and the following weekend, the first lady of UK wine, Jancis Robinson, unburdens herself on “the most frightening period of my professional life” – judging last year’s Old Mutual Trophy Wine Show. Her elegantly crafted account appeared in the Financial Times. I covered the same events in a more sideways fashion on page 46 of Sour Grapes, reproduced below:

The most bizarre tsunami in the SA wine spittoon occurred last year when a short story of Nikolai Gogol played out in the winelands.

The profession of food taster is a noble one, with several giving their lives to protect their employer. Screenwriter Peter Elbling had a best seller on his hands with the Food Taster, a surreal faux-memoir of a 16th century Italian food taster Ugo DiFonte, defending his employer, the corrupt Duke Federico Basillione DiVincelli, against such Hunter S Thompson-esque poisons as the saliva of a pig hung upside down and beaten until it went mad.

Fidel Castro had one and Polonium victim Alexander Litvinenko could have done with one. The Borgias used them extensively as did the Russian royals. Which sets the scene for Nikolai Gogol’s surreal story of Collegiate Assessor Kovalyov, who wakes one morning to discover his nose missing.

Set in St. Petersburg, Kovalyov’s nose turns up in the breakfast roll of his barber who tosses it into the River Neva. The nose decides to pursue an independent career and finds employment as a state councilor with elegant carriage and a smart uniform. A bit like the cosy club of international wine judges in their Blundstones and Issy Miyakes in Business Class (at least), which has superseded the elegant carriages of yore.

Gogol’s surreal story could be the reason Robert Parker has insured his own proboscis for $1 million. For without it, Parker would be like Kovalyov who battled to have his opinions taken seriously sans nez. Which may have been one of the motivations behind Dutch winemaker and musician Ilya Gort insuring his proboscis for R60 million earlier this year with Lloyd’s of London.

Owner of Château de la Garde in Bordeaux, Gort’s wine was voted best Bordeaux wine of 2003 at the International Wine Challenge in London. He is also a published author: Het Wijnsurvivalboek is one of his. With coffee and mocha popular flavours in SA Shiraz, the news that his advertising jingles for Nescafé are flighted in 160 countries around the world confirm he is no loose cannon. Even if his most famous composition, wildly popular in the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany (all important SA wine export destinations now that SA producers are advised to retreat from the USA by the exporter’s association) is called “Don’t come stoned and don’t tell Trude”, written for the duo Max & Specs. Although just who Trude is remains a mystery – his wife rejoices in the name Turf.

While insuring your sharp end might be dismissed as PR-grandstanding along the lines of Betty Grable insuring her legs for a bar or Dolly Parton her 106cm embonpoint for $600 000, losing your sense of smell does happen.

Ask Bernd Philippi, voted Germany’s top winemaker in Feinschmekker magazine for his iconic Saumagen (sow’s stomach) Riesling, who lost his when he banged the back of his head during a fall. A whiz at blending and responsible for the 2001 Mont du Toit Decanter magazine hailed as the best SA Bordeaux blend (embarrassing Shiraz component notwithstanding) and which impressed the zum jug sommelier so, Philippi now relies on flavour and the tactile impression of viscosity, although his nasal acuity is slowly returning.

Of course many are fervently hoping that Parker’s insurers will have to cough up. Philosopher Roger Scruton, who writes the most erudite wine column in the business for New Statesman magazine, noted “thanks to Nosy Parker, the entire market in wine has been surrendered to the phony expertise of the modern oenophile, which consists in writing execrable prose about flavours, awarding arbitrary points and pretending to be a nose about town.”

Scruton’s main gripe is that application of Parker’s proboscis reduces centuries of French tradition, mystique and terroir to a common denominator which may be compared with the brash New World. No bad thing, some would say. My own problem is not with Parker’s schnozzle per se (and judging by photographs, it’s an outwardly inoffensive organ), just the fact that his is the only nose in town.

With John Platter now moved on to better things like rounds of golf in Kwazulu-Natal, SA has no serious contender for a R1 million “nose about town” as imports are quoted along with their Parker ratings brought down from the mountain and local recommendations are usually the result of committee decisions of wine shows and magazine tasting panels. Platter’s personal proboscis has been replaced by a dodgy panel of “professional” hooters. Around two dozen in number, they come in all shapes and sizes, with the handful of annual wine guides featuring the opinions of a subset, played out across multiple publications. While not as extreme as the Parker mono-nose model, the lack of nasal diversity is an issue.

Parker highlights “the growing international standardization of wine styles” as issue #1 in his Wine Buyer’s Guide while reflecting on “the Dark Side of Wine”, a standardization he ironically has done most to advance through his overwhelming dominance in the business of compiling liquid laundry lists.

If you accept that variety, as well as being the spice of life, is one of the features that makes wine more exciting than premixed cocktails and ready-to-drinks, where are the new noses for sniffing out icons, to come from? Perhaps the burgeoning restaurant scene playing out in a shopping centre near you, holds the key. With more wine dinners and chefs tables than you can shake a swizzle stick at, perhaps the time has come for the opinions of sommeliers, maîtres d’ and chefs to achieve wider currency. They certainly can’t do any worse than the present lot.

The public is heartily sick and tired of show-off noses, if the theft of a statue to Gogol’s nose in St. Petersburg is anything to go by. The 100 Kg marble schnozzle “seems to have gone for a walk” according to its sculptor Vyacheslav Bukhayev. “I really don’t know who could have taken it – maybe it was some art lover who prefers admiring works of art in private.”

After a smash hit with Mozart’s Magic Flute opera in 2007, Artthrob reports that the darling of the corporate art collection, William Kentridge, is now working towards a 2010 production of Shostakovich’s opera the Nose at the Met in New York. If six winemakers were prepared to shell out R50 000 each for the rights to use a Flute image as label, how much more will they pay to embrace his Nose?

But the R50 000 question ignored by Gogol and Shostakovich is what did Kovalyov do in the interim before he was reunited with his shnoz? Moonlight as a wine judge? At the 2007 outing of the Toasty Show, a British Master of Wine of mega gravitas rated more than a gross of Shiraz “with no sense of smell whatever” and there’s been a funny smell in the air ever since. “My sore throat turned into one of the worst flu-ey colds I can remember” this Kovalyov de nos jours confided to the purple subscription-only pages of her website.

Instead of retiring injured, claiming against the insurance policy, or at least keeping mum, she valiantly pressed on and did it all by mouth. As she remarked “it has been really interesting to have my senses focussed (sic) on the structure of each wine and on what you can sense only with the palate” which must have caused much gnashing of teeth and wailing among the Pinelands Pundits of WINE magazine who had to print her comments on SA wine with a straight face. Producers were not best pleased.

The comments of La Kovalyov fly in the face of perceived wisdom with authorities like the first philosopher of taste since Epicurus, renowned French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, who recognized the importance of smell back in 1825 in his landmark Physiology of Taste. “I am not only convinced that without the cooperation of smell there can be no complete degustation” he noted, “but I am also tempted to believe that smell and taste are in fact but a single sense, whose laboratory is in the mouth and whose chimney is the nose; or to be more precise, in which the mouth performs the degustation of the tactile bodies, and the nose the degustation of the gases.”

It’s self-evident that food and drink looses its flavour and appeal when you’re sick with ‘flu so the argument that the MW in question was so experienced she could evaluate wines without being able to smell them (while taking anti-decongestants at the same time) is clearly a spurious one.

Removing the sense of smell from the equation really does transform any tasting into a blind one, although perhaps not quite in the way producers paying close to R1000 to enter their wines into the competition, would appreciate. Richard Dawkins’ blind watchmaker of evolution certainly kicks up a stink: four genes are associated with the sense of sight while more than one thousand are necessary to nail down smell.

Smell is the least developed of our senses and is the only one that gets piped directly into those centres of the brain that deal with memory and emotion. The others get censored by the thalamus and then are passed on to the cortex for further processing.

Our human sensory world is dominated by the visual and even taste gets a better press than smell: restaurant menus surrender to paroxysms of delight when describing flavours of a dish, but are uncharacteristically coy on the subject of smell.

A recent new theory on the physical mechanics of smell, the Secret of Scent (Faber & Faber, 2006) by Luca Turin, proposes that we recognize smells by sensing the vibration of molecules, rather than sensing the shape of aromatic molecules via nasal Velcro. From a philosophical point of view this gives a warm and satisfying feeling as those other two remote senses, sight and sound, also take place in the vibrational plane.

The lock-and-key hypothesis was clearly never going to work unaided as there are exactly 347 different human odour receptors while we can typically differentiate many thousands of different smells. However, the vibration theory is clearly not the last word either as research published in Nature Neuroscience in 2004 reported that volunteers could not distinguish between molecules with different atomic vibrations but the same shape. So while the scientific jury continues to be out considering its verdict, speculation on the mechanics of smell continues unabated.

One of the more intriguing claims in Turin’s book is that at least one Champagne producer adds an illegal scent “to boost brand loyalty.” But while Turin’s book is written by the scientist who did most of the heavy lifting and made the major breakthroughs, a more accessible book on the subject is the Emperor of Scent (Random House, 2003) by Chandler Burr. The title anticipates the Emperor of Wine (Ecco, 2005), Elin McCoy’s biography of Robert Parker, America’s million dollar nose.

Burr is well qualified for the job of explicator as he’s also the first perfume critic at the New York Times with a bi-monthly column called Scent Notes that rates perfumes on a Platter’s five star scale, sighted, again just like Platter’s. Judging by his column, the world of perfume is even more highly charged than the observations of a fevered wine anorak with participants like designer Tom Ford “dreaming of a perfume that smelled like fresh cherry wood licked by a green-hot oxygen fire in a Balinese temple.”

Burr himself demonstrates a clean pair of winespeak heals in a column called Men Smelling Badly: “Osmanthe Yunnan smells like a field of hay: you inhale summer sunlight, perhaps some dry straw, clover and honey. It also smells (and there’s no other way to describe it) bizarrely more human than that — as if these earthly delights had been caught on the sweaty skin of the young man harvesting that field. Jean-Claude Ellena, the Hermès perfumer, has taken this complex tonality and built out of it a scent the way a master carpenter turns raw oak into a perfect, linear, quietly masculine chest of drawers. The experience of smelling it is like that of listening to an orchestra tuning up: dozens of instruments intent on finding their own perfect balance, a scattering of notes, and then the composer taps the podium.”

All the usual winespeak bases are gracefully covered: gratuitous anthropomorphism, linearity, musical analogues while gracefully dropping the name of the perfumier in the process.

Turin clears up many misconceptions and makes some important points like how come smokers are often more precise nosers than non-smokers. The late SFW MD Ronnie Melck was a famous puffer and ace taster and Anthony Hamilton Russell is no slouch in the sniffing, swirling and spitting stakes in spite of a serious Hoyo de Monterey habit. Bernd Phillipi was likewise a sharp tasting Marlboro Man for decades.

Turin claims the carbon monoxide in cigarette smoke totally blocks the enzyme cytochrome P450 which breaks down smell molecules with the result that they persist in the nose, improving smell. All music to the ears of Johann Rupert, SA King of Tobacco, with a much anticipated and headily aromatic L’Ormarins red blend, waiting in the wings.

The second shibboleth blown up faster than a Gauteng ATM is the idea that smell is primarily to do with sex. As Turin notes “smell is not about sex, contrary to popular belief, it’s about food and protection from decaying, poisonous things that can hurt you.” Which doesn’t explain the anecdote of Somerset Maugham explaining the success the fat and homely HG Wells had with women. “I once asked one of his mistresses what especially attracted her to him. I expected her to say his acute mind and sense of fun; not at all; she said that his body smelt of honey.”

Another intriguing idea is that smells are objectively real – the olfactory experience of MWs and civilians to a glass of Shiraz is the same, although acuity does decline with advancing age (50 seems to be the threshold to the slopes of anosmia), which could explain the variability of blind tasting results featuring mature tasters – as most local ones are on the angel’s side of 50. As Turin notes “Oh, to hell with, ‘expertise’! – it doesn’t exist!” A sentiment shared by many unhappy wine show participants.

But perhaps the most intriguing feature of the new theory is the accommodation for superposition of smells. Turin notes that the aroma (and hence taste) of caraway consists of mint and cabonyl (aka acetone or nail varnish remover). So blending a minty Thelema Merlot with a rustic Jacobsdal Pinotage should produce a spicy Cape Blend with a distinct aniseed flavour. Which opens up endless blending possibilities and the possibility of designer wines assembled from a fragrant palate of aromatic ingredients.

Reviewing the Secret of Scent in the Guardian, Alex Butterworth concludes “Turin is a true amateur whose conspicuous sincerity is refreshing in an age of constructed passions and marketing.” Just the kind of decongestant SA wine needs to clear the pipes clogged by conflicts of interest and terminal cultural cringe.

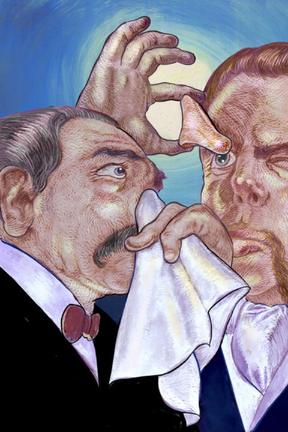

While a clear nose is a necessary prerequisite for choosing wine by smell, La Kovalyov’s indisposition did have its funny side. Proust was something of an expert on taste and smell with madeleines dunked in lime tea a firm favourite, but above all, he was a snob. A sharp dresser (James Joyce, author of Ulysses, Amazon.com’s “favourite novel of the 20th century”, said he looked like the hero of The Sorrows of Satan), he was also a hypochondriac, whose lucky break arrived in early 1919 when he caught a head cold from the British ambassador, Lord Derby, memorably described by Lloyd George as looking “like a harpooned walrus.”

As a friend noted, “the English cold lasted all spring, which gave him a thousand opportunities to mention Lord Derby, which he liked to do often.” The ‘flu of La Kovalyov was clearly a direct descendent of Lord Derby’s cold among fashionable Cape anoraks with a photograph of her at Chamonix in Franschhoek, tissue firmly clutched in hand, given pride of place on the homepage of Grape website www.grape.org.za for days.

All things considered, M. Proust would have made a formidable wine judge along the lines of a refined version of Robert Parker, but thankfully wine competitions were unknown in the Paris of the roaring twenties. As indeed they remain to this day.

Yet there is a strange SA connection to Proust. The love of his life was a young chauffeur-cum-mechanic called Alfred Agostinelli who would take his employer on country jaunts at night, shining his headlights so the great soul could admire the roses.

Could Alfred be related to Michele Agostinelli who arrived in SA in 1940 as an Italian prisoner of war? Fairview owner Charles Back credits his Agostinelli with establishing the burgeoning Fairview cheese business and remembers him in a range of exciting wines made from classic Italian varietals like Sangiovese and Barbera.

The cheese maker certainly had a happier life than his namesake who died when he crashed the plane that Proust had bought him into the Mediterranean off Antibes, on his second solo flight. Unable to swim, “clinging to the wreckage he made pitiful gestures for help, but drowned before rescuers could reach him.” As Stevie Smith might have said “not waving but drowning.”